Warriors' Tales, Memoirs and Letters

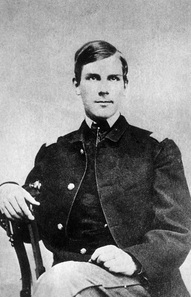

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Memorial Day Speech (Excepts)

We have shared the incommunicable experience of War. We felt—we still feel—the passion of life to its top. The generation that carried on the war has been set apart by its experience. In our youths, our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing.

1st Lieutenant, 20th Massachusetts Regiment, 1862-1866

Justice of the United States Supreme Court, 1902--1932

Sam Watkins

Sam Watkins

Sam Watkins

Co. "Aytch"

Maury Grays, First Tennessee Regiment

or, A Side Show of the Big Show

(Except)

By

Sam R. Watkins

Corporal, 1st Tennessee Regt.

"STANDING PICKET ON THE POTOMAC"

Leaving Winchester, we continued up the valley.

The night before the attack on Bath or Berkly Springs, there fell the largest snow I ever saw.

Stonewall Jackson had seventeen thousand soldiers at his command. The Yankees were fortified at Bath. An attack was ordered, our regiment marched upon top of a mountain overlooking the movements of both armies in the valley below. About 4 o'clock one grand charge and rush was made, and the Yankees were routed and skedaddled.

By some circumstance or other, Lieutenant J. Lee Bullock came in command of the First Tennessee Regiment. But Lee was not a graduate of West Point, you see.

The Federals had left some spiked batteries on the hill side, as we were informed by an old citizen, and Lee, anxious to capture a battery, gave the new and peculiar command of, "Soldiers, you are ordered to go forward and capture a battery; just piroute up that hill; piroute, march. Forward, men; piroute carefully." The boys "pirouted" as best they could. It may have been a new command, and not laid down in Hardee's or Scott's tactics; but Lee was speaking plain English, and we understood his meaning perfectly, and even at this late day I have no doubt that every soldier who heard the command thought it a legal and technical term used by military graduates to go forward and capture a battery.

At this place (Bath), a beautiful young lady ran across the street. I have seen many beautiful and pretty women in my life, but she was the prettiest one I ever saw. Were you to ask any member of the First Tennessee Regiment who was the prettiest woman he ever saw, he would unhesitatingly answer that he saw her at Berkly Springs during the war, and he would continue the tale, and tell you of Lee Bullock's piroute and Stonewall Jackson's charge.

We rushed down to the big spring bursting out of the mountain side, and it was hot enough to cook an egg. Never did I see soldiers more surprised. The water was so hot we could not drink it.

The snow covered the ground and was still falling.

That night I stood picket on the Potomac with a detail of the Third Arkansas Regiment. I remember how sorry I felt for the poor fellows, because they had enlisted for the war, and we for only twelve months. Before nightfall I took in every object and commenced my weary vigils. I had to stand all night. I could hear the rumblings of the Federal artillery and wagons, and hear the low shuffling sound made by troops on the march. The snow came pelting down as large as goose eggs. About midnight the snow ceased to fall, and became quiet. Now and then the snow would fall off the bushes and make a terrible noise. While I was peering through the darkness, my eyes suddenly fell upon the outlines of a man. The more I looked the more I was convinced that it was a Yankee picket. I could see his hat and coat—yes, see his gun. I was sure that it was a Yankee picket. What was I to do? The relief was several hundred yards in the rear. The more I looked the more sure I was. At last a cold sweat broke out all over my body. Turkey bumps rose. I summoned all the nerves and bravery that I could command, and said: "Halt! who goes there?" There being no response, I became resolute. I did not wish to fire and arouse the camp, but I marched right up to it and stuck my bayonet through and through it. It was a stump. I tell the above, because it illustrates a part of many a private's recollections of the war; in fact, a part of the hardships and suffering that they go through.

Maury Grays, First Tennessee Regiment

or, A Side Show of the Big Show

(Except)

By

Sam R. Watkins

Corporal, 1st Tennessee Regt.

"STANDING PICKET ON THE POTOMAC"

Leaving Winchester, we continued up the valley.

The night before the attack on Bath or Berkly Springs, there fell the largest snow I ever saw.

Stonewall Jackson had seventeen thousand soldiers at his command. The Yankees were fortified at Bath. An attack was ordered, our regiment marched upon top of a mountain overlooking the movements of both armies in the valley below. About 4 o'clock one grand charge and rush was made, and the Yankees were routed and skedaddled.

By some circumstance or other, Lieutenant J. Lee Bullock came in command of the First Tennessee Regiment. But Lee was not a graduate of West Point, you see.

The Federals had left some spiked batteries on the hill side, as we were informed by an old citizen, and Lee, anxious to capture a battery, gave the new and peculiar command of, "Soldiers, you are ordered to go forward and capture a battery; just piroute up that hill; piroute, march. Forward, men; piroute carefully." The boys "pirouted" as best they could. It may have been a new command, and not laid down in Hardee's or Scott's tactics; but Lee was speaking plain English, and we understood his meaning perfectly, and even at this late day I have no doubt that every soldier who heard the command thought it a legal and technical term used by military graduates to go forward and capture a battery.

At this place (Bath), a beautiful young lady ran across the street. I have seen many beautiful and pretty women in my life, but she was the prettiest one I ever saw. Were you to ask any member of the First Tennessee Regiment who was the prettiest woman he ever saw, he would unhesitatingly answer that he saw her at Berkly Springs during the war, and he would continue the tale, and tell you of Lee Bullock's piroute and Stonewall Jackson's charge.

We rushed down to the big spring bursting out of the mountain side, and it was hot enough to cook an egg. Never did I see soldiers more surprised. The water was so hot we could not drink it.

The snow covered the ground and was still falling.

That night I stood picket on the Potomac with a detail of the Third Arkansas Regiment. I remember how sorry I felt for the poor fellows, because they had enlisted for the war, and we for only twelve months. Before nightfall I took in every object and commenced my weary vigils. I had to stand all night. I could hear the rumblings of the Federal artillery and wagons, and hear the low shuffling sound made by troops on the march. The snow came pelting down as large as goose eggs. About midnight the snow ceased to fall, and became quiet. Now and then the snow would fall off the bushes and make a terrible noise. While I was peering through the darkness, my eyes suddenly fell upon the outlines of a man. The more I looked the more I was convinced that it was a Yankee picket. I could see his hat and coat—yes, see his gun. I was sure that it was a Yankee picket. What was I to do? The relief was several hundred yards in the rear. The more I looked the more sure I was. At last a cold sweat broke out all over my body. Turkey bumps rose. I summoned all the nerves and bravery that I could command, and said: "Halt! who goes there?" There being no response, I became resolute. I did not wish to fire and arouse the camp, but I marched right up to it and stuck my bayonet through and through it. It was a stump. I tell the above, because it illustrates a part of many a private's recollections of the war; in fact, a part of the hardships and suffering that they go through.

Sullivan Ballou's Letter Home

July

14, 1861

Camp Clark

Washington D.C.

My very dear Sarah:

The indications are very strong that we shall move in a few days—perhaps tomorrow. Lest I should not be able to write again, I feel impelled to write a few lines that may fall under your eye when I shall be no more . . .

I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American Civilization now leans on the triumph of the Government and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and sufferings of the Revolution. And I am willing—perfectly willing—to lay down all my joys in this life, to help maintain this Government, and to pay that debt . . .

Sarah my love for you is deathless, it seems to bind me with mighty cables that nothing but Omnipotence could break; and yet my love of Country comes over me like a strong wind and bears me irresistibly on with all these chains to the battle field.

The memories of the blissful moments I have spent with you come creeping over me, and I feel most gratified to God and to you that I have enjoyed them for so long. And hard it is for me to give them up and burn to ashes the hopes of future years, when, God willing, we might still have lived and loved together, and seen our sons grown up to honorable manhood, around us. I have, I know, but few and small claims upon Divine Providence, but something whispers to me—perhaps it is the wafted prayer of my little Edgar, that I shall return to my loved ones unharmed. If I do not my dear Sarah, never forget how much I love you, and when my last breath escapes me on the battle field, it will whisper your name. Forgive my many faults and the many pains I have caused you. How thoughtless and foolish I have often times been! How gladly would I wash out with my tears every little spot upon your happiness . . .

But, O Sarah! If the dead can come back to this earth and flit unseen around those they loved, I shall always be near you; in the gladdest days and in the darkest nights . . . always, always, and if there be a soft breeze upon your cheek, it shall be my breath, as the cool air fans your throbbing temple, it shall be my spirit passing by. Sarah do not mourn me dead; think I am gone and wait for thee, for we shall meet again . . .

[Sullivan Ballou was killed a week later at the first Battle of Bull Run, July 21, 1861]

Courtesy of PBS.org by permission.

Camp Clark

Washington D.C.

My very dear Sarah:

The indications are very strong that we shall move in a few days—perhaps tomorrow. Lest I should not be able to write again, I feel impelled to write a few lines that may fall under your eye when I shall be no more . . .

I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American Civilization now leans on the triumph of the Government and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and sufferings of the Revolution. And I am willing—perfectly willing—to lay down all my joys in this life, to help maintain this Government, and to pay that debt . . .

Sarah my love for you is deathless, it seems to bind me with mighty cables that nothing but Omnipotence could break; and yet my love of Country comes over me like a strong wind and bears me irresistibly on with all these chains to the battle field.

The memories of the blissful moments I have spent with you come creeping over me, and I feel most gratified to God and to you that I have enjoyed them for so long. And hard it is for me to give them up and burn to ashes the hopes of future years, when, God willing, we might still have lived and loved together, and seen our sons grown up to honorable manhood, around us. I have, I know, but few and small claims upon Divine Providence, but something whispers to me—perhaps it is the wafted prayer of my little Edgar, that I shall return to my loved ones unharmed. If I do not my dear Sarah, never forget how much I love you, and when my last breath escapes me on the battle field, it will whisper your name. Forgive my many faults and the many pains I have caused you. How thoughtless and foolish I have often times been! How gladly would I wash out with my tears every little spot upon your happiness . . .

But, O Sarah! If the dead can come back to this earth and flit unseen around those they loved, I shall always be near you; in the gladdest days and in the darkest nights . . . always, always, and if there be a soft breeze upon your cheek, it shall be my breath, as the cool air fans your throbbing temple, it shall be my spirit passing by. Sarah do not mourn me dead; think I am gone and wait for thee, for we shall meet again . . .

[Sullivan Ballou was killed a week later at the first Battle of Bull Run, July 21, 1861]

Courtesy of PBS.org by permission.