Songs of Protests and Freedom

Music and song was integral to the lives of slaves. Songs were used to aid the brutal work demanded. Work songs were often led by a leader, followed by repetition of the lines by the group. This technique is known as 'lining.' A similar thing occurred on sailing vessels; the crews sang 'pulling' songs in a similar fashion to raise sails and anchors.

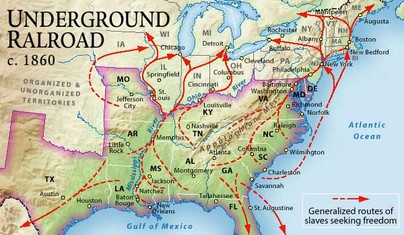

Slave owners forbade the use of African-based music while allowing--often encouraging--slaves to sing Christian music and play traditional European and American instruments. The result became known as the Negro Spiritual. These songs, however, went beyond the level of worship (and they certainly were that); they expressed the hope and desire for freedom. Some songs become codes, directions for passage on the Underground Railroad. A number of these songs have entered into American Gospel & Folk music traditions. Examples include "Michael Row the [your] Boat Ashore" and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot."

Like any material founded by Oral Traditions, dating and validation by historical and academic authorities is uneven. One example is "Follow the Drinking Gourd." The first known publication of the song is 1928, causing a number of scholars to doubt that the song is what tradition tells us: the song gives directions to follow and cross the Ohio River to be ferried to freedom by the Captain, Jack. However, the musicians maintain that they heard it sung by Black singers who were either former slaves or off springs of slaves. The lyrics have been scrutinized by historians to be denied or considered valid and accurate. NASA's website validates the 'map' the lyrics provide, devoting an entire webpage to the song's accuracy.

I accept the tradition as legitimate.

Slave owners forbade the use of African-based music while allowing--often encouraging--slaves to sing Christian music and play traditional European and American instruments. The result became known as the Negro Spiritual. These songs, however, went beyond the level of worship (and they certainly were that); they expressed the hope and desire for freedom. Some songs become codes, directions for passage on the Underground Railroad. A number of these songs have entered into American Gospel & Folk music traditions. Examples include "Michael Row the [your] Boat Ashore" and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot."

Like any material founded by Oral Traditions, dating and validation by historical and academic authorities is uneven. One example is "Follow the Drinking Gourd." The first known publication of the song is 1928, causing a number of scholars to doubt that the song is what tradition tells us: the song gives directions to follow and cross the Ohio River to be ferried to freedom by the Captain, Jack. However, the musicians maintain that they heard it sung by Black singers who were either former slaves or off springs of slaves. The lyrics have been scrutinized by historians to be denied or considered valid and accurate. NASA's website validates the 'map' the lyrics provide, devoting an entire webpage to the song's accuracy.

I accept the tradition as legitimate.

|

Follow the Drink Gourd

Traditional Date Unknown CHORUS Follow the drinking gourd, follow the drinking gourd For the old man is a-waitin' to carry you to freedom Follow the drinking gourd When the sun goes back and the first quail calls Follow the drinking gourd The old man is a-waitin' for to carry you to freedom Follow the drinking gourd CHORUS The river bed makes a mighty fine road, Dead trees to show you the way And it's left foot, peg foot, traveling on Follow the drinking gourd CHORUS The river ends between two hills Follow the drinking gourd There's another river on the other side Follow the drinking gourd CHORUS I thought I heard the angels say Follow the drinking gourd The stars in the heavens gonna show you the way Follow the drinking gourd CHORUS Source: Negro Spirituals.com |

|

My Old Kentucky Home (1853)

Stephen Collins Foster

What at first may seem an unlikely song by an unlikely composer is "My Old Kentucky Home" by Stephen Foster.

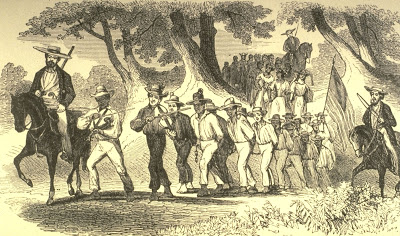

Best known during his time for writing for Black Face or Minstrel Shows, Foster was no bigot in the usual sense, although sharing mainstream ideas of white racial superiority. Naive about life on Southern plantation and working conditions of slaves, Foster was struck hard by Uncle Tom's Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe (whom Abraham Lincoln once, jesting, referred to as the little lady who started this Great War). A delayed honeymoon in 1852 took Foster and his wife down the River to New Orleans and Mardi Gras. He watched slaves working in fields during his travels and encountered slavery first hand in New Orleans. When confronted with reality, Foster revealed a passionate and compassionate nature. His ballad "Hard Times Come Again no More" is such an example. This thoughtful song tells a story of an unnamed slave being "sold South" to Louisiana sugar cane fields, which is a practical death sentence.

"My Old Kentucky Home" provided a voice in song for Abolitionists, though not Foster's intention. It moved many, not just in the North and not just white Americans. Frederick Douglas loved the song, saying it displays the heartbreak that nearly every slave felt upon being sold and uprooted from family, friends, and place (Foster wrote the first American song, written by a white composer, "Nellie was a Lady," in which an African-American woman is addressed as a 'lady'). Southerners, too, embraced it; the sense of dislocation, the loss of home, and separation from family resonated with Southern sentiments as well. Such was the song's force that is was a major factor in the slave state Kentucky's decision to remain in the Union and not join the Confederacy.

"My Old Kentucky Home" is the anthem used at the annual Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs, one of the few songs sung before a major sporting event other than the "Star Spangled Banner."

Stephen Collins Foster

What at first may seem an unlikely song by an unlikely composer is "My Old Kentucky Home" by Stephen Foster.

Best known during his time for writing for Black Face or Minstrel Shows, Foster was no bigot in the usual sense, although sharing mainstream ideas of white racial superiority. Naive about life on Southern plantation and working conditions of slaves, Foster was struck hard by Uncle Tom's Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe (whom Abraham Lincoln once, jesting, referred to as the little lady who started this Great War). A delayed honeymoon in 1852 took Foster and his wife down the River to New Orleans and Mardi Gras. He watched slaves working in fields during his travels and encountered slavery first hand in New Orleans. When confronted with reality, Foster revealed a passionate and compassionate nature. His ballad "Hard Times Come Again no More" is such an example. This thoughtful song tells a story of an unnamed slave being "sold South" to Louisiana sugar cane fields, which is a practical death sentence.

"My Old Kentucky Home" provided a voice in song for Abolitionists, though not Foster's intention. It moved many, not just in the North and not just white Americans. Frederick Douglas loved the song, saying it displays the heartbreak that nearly every slave felt upon being sold and uprooted from family, friends, and place (Foster wrote the first American song, written by a white composer, "Nellie was a Lady," in which an African-American woman is addressed as a 'lady'). Southerners, too, embraced it; the sense of dislocation, the loss of home, and separation from family resonated with Southern sentiments as well. Such was the song's force that is was a major factor in the slave state Kentucky's decision to remain in the Union and not join the Confederacy.

"My Old Kentucky Home" is the anthem used at the annual Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs, one of the few songs sung before a major sporting event other than the "Star Spangled Banner."

|

The sun shines bright in the old Kentucky home.

'Tis summer, the darkies [people] are gay, The corn top's ripe and the meadow's in the bloom While the birds make music all the day. The young folks roll on the little cabin floor, All merry, all happy and bright. By 'n by hard times comes a-knocking at the door, Then my old Kentucky home, good night. Weep no more my lady, oh! weep no more today! We will sing one song for the old Kentucky home, For the old Kentucky home far away. They hunt no more for the 'possum and the coon, On the meadow, the hill and the shore, They sing no more by the glimmer of the moon, On the bench by that old cabin door. The day goes by like a shadow o'er the heart, With sorrow where all was delight. The time has come when the darkies [people] have to part, Then my old Kentucky home, good night! Weep no more my lady, oh! weep no more today! We will sing one song for the old Kentucky home, For the old Kentucky home far away. The head must bow and the back will have to bend, Wherever the darkey [people] may go. A few more days and the trouble all will end, In the field where the sugar-canes may grow. A few more days for to tote the weary load, No matter 'twill never be light. A few more days till we totter on the road, Then my old Kentucky home, good night. Weep no more my lady, oh! weep no more today! We will sing one song for the old Kentucky home, For the old Kentucky home far away. Source: The Stephen Foster Songbook. (Dover Press) |

Songs of Weary Souls

Like much of the slave culture, the dreariness of life was often disguised. Few slaves were allowed expression on almost all subjects, including sadness and despair. As recorded in the landmark book on slavery in the United States, The Peculiar Institution, slaves told the plantation owners what they (the owners) wanted wished to hear: life was good in slavery and they, the slaves, had no desire to be free. Religious expression, however, was encouraged. The religious songs sung were bound up by the life in bondage, allowing emotional and spiritual release.

Like many songs and stories, they were not written down until after the Civil War, making hard documentation difficult. Yet, they flowed into the new national culture. A number of these songs are now found in numerous hymnbooks.

Like many songs and stories, they were not written down until after the Civil War, making hard documentation difficult. Yet, they flowed into the new national culture. A number of these songs are now found in numerous hymnbooks.

Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child

Music and Lyrics: Unknown

The first known performance was by the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1870, also the year of its first publication.

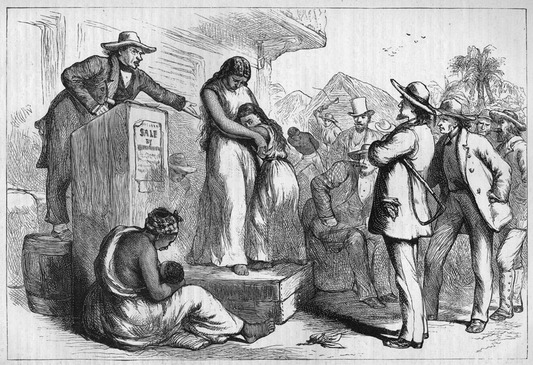

Slave Mother At Auction

Slave Mother At Auction

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child

A long ways from home

A long ways from home

True believer

A long ways from home

Along ways from home

Sometimes I feel like I’m almos’ gone

Sometimes I feel like I’m almos’ gone

Sometimes I feel like I’m almos’ gone

Way up in de heab’nly land

Way up in de heab’nly land

True believer

Way up in de heab’nly land

Way up in de heab’nly land

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child

A long ways from home

There’s praying everywhere

Source: American Negro Spirituals by J. W. Johnson, Boston: J. R. Johnson, 1926. Ebook. Openlibrary.org. Web. August 2015.

Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen

Music and Lyrics: Unknown

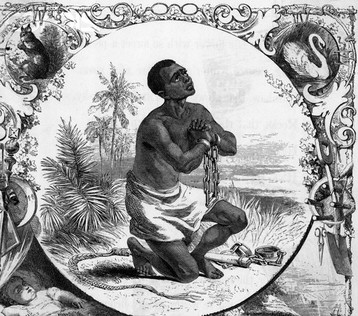

Slave at the end of the slave trade, praying.

Slave at the end of the slave trade, praying.

Chorus:

Nobody knows de trouble I’ve seen

Nobody knows de trouble but Jesus

Nobody knows de trouble I’ve seen

Glory Hallelujah!

Sometimes I’m up, sometimes I’m down

Oh, yes, Lord

Sometimes I’m almost to de groun’

Oh, yes, Lord

Although you see me goin’ ‘long so

Oh, yes, Lord

Chorus

I have my trials here below

Oh, yes, Lord

If you get there before I do

Oh, yes, Lord Tell all-a my friends I’m coming too

Oh, yes, Lord

Chorus

Nobody knows de trouble I’ve seen

Nobody knows de trouble but Jesus

Nobody knows de trouble I’ve seen

Glory Hallelujah!

Sometimes I’m up, sometimes I’m down

Oh, yes, Lord

Sometimes I’m almost to de groun’

Oh, yes, Lord

Although you see me goin’ ‘long so

Oh, yes, Lord

Chorus

I have my trials here below

Oh, yes, Lord

If you get there before I do

Oh, yes, Lord Tell all-a my friends I’m coming too

Oh, yes, Lord

Chorus

Source: Slave Songs of the United States. Eds. William Allen, et al. Boston: Ware, 1867. Microfiche.