Parlor Music, Minstrel Shows, Music Hall, Folk Songs and Gospel

Popular music flourished during the Romantic Period and the Civil War. America failed to produce classical composers with the quality of Strauss, Wagner, or Verde, but the popular music field gave birth to composers and poets who produced a wealth of tunes, lyrics, and traditions that resonate to this day. The roots of jazz, screen and stage soundtracks, the Blues, and rock and roll have their origins from this period. Of course, these forms of music do have deep roots from Europe and African, but they developed in the rich soil of the New World. Nevertheless, it was during this time that an American musical identity became established.

It is important to remember that these divisions are, in some ways, arbitrary. It very common to find parlor songs, for example, performed in Saloon Halls, Opera Houses, on the Oregon and Sante Fe Trails, and (religious songs) in churches. The crossovers were common.

Parlor Music is a form with roots in the 18th century. This activity seems almost too hokey to be real, but it provided pleasure and enjoyment for millions. Small groups of family and/or friends would perform, in their parlors of course, music that is melody centered. Various (or none) musical instruments would accompany the vocals. Often, music was strictly instrumental or vocal only. The music was commonly for a single voice (alto or tenor) with piano accompaniment. However, the music was adaptable for various instruments. Stephen Foster's music was uncommon, for he often wrote choruses for 4 part harmony. The high demand for music maintained music publishers all throughout America. Parlor music gave rise to the first true American music. Many songs were adapted for public performances. Some composers, like Foster, wrote songs that went easily from Parlor to Saloon Hall to Minstrel Show.

Some music and lyrics go back to the Revolutionary War and War of 1812 periods. One example is "Johnnie has Gone for a Soldier," which has roots in Ireland or Scotland (there's argument here; perhaps found in both?). The Scottish immigrants were more numerous and actively involved in the Revolution than the Irish, so I think the song came to the New World from Scotland even if it originated in Ireland. Regardless, this beautiful lament remains well known here at the beginning of the 21st century. The lyrics sung by Erin Ivey (below) are one of the many versions available, but the words are very close. Minor changes in lyrics, melody, and rhythm by each performer is a norm in the world of music performance.

Minstrel Shows seem to us today as unbelievable or even impossible. The right and wrong of it is not the discussion here. The Minstrel Show was also known as "Black Face," for white musicians and actors would paint their faces black in imitation of African-Americans -- particularly of those who were enslaved. These shows were performances although the songs frequently were published and sung in parlors as well as Music Halls. Minstrel Shows were first recorded in a music hall when Tom Rice Dixon, it is said, literally borrowed the clothes from a Black laborer, charcoled his face to perform an "Ethiopian" song. Many composers, however, were familiar with the church and secular music of free blacks. This was an influence, not copying as Modernist musicians argued in the 1930's. Stephen Foster, as an example, irritated his parents by sneaking off to listen to the Black laborers and performers near the docks and warehouses near his home. A free-Black maid in the Foster house often took the child Foster with her to local AME church services. This influence would be similar to the effects the Blues had upon the young Elvis Presley. During the first half of the 19th century, the minstrel shows went through three phases. In phase one, the performers presented skits and songs, while denigrating African Americans as ignorant and childlike, also rediculed Irish and German immigrants and the upper classes of the Industrial Revolution. In the second phase, the shows became more gentile for various reasons. The minstrel producer E. P. Christie and his Christie Minstrels and others wanted a broader more gentile paying audience than had been before. This coincides with Stephen Foster's attitude shifts. In partnership with Christie his music presents a human and sympathetic person. Examples of his songs include "Nellie Was A Lady," "My Old Kentucky Home." and "Old Folks at Home." Phase three in the mid to late 1850's turned vicious as tensions just before the Civil War heated up. At this point Foster quit writing his Plantation Songs and Christie retired.

Incredibly, these types of shows remained popular through the early 1960's [I myself took part of one these programs in grade school program in the sixth grade in Denton, TX. I was the only child not in black face as I was the 'ringmaster']. The BBC had a variety series, Black and White, that continued this tradition to the 1970's. The first important 'talking' movie was The Jazz Singer in which the finale is a black face performance by Al Jolson. Was this musical form racist? Of course it was. Nonetheless, many classic tunes that we are familiar with have roots here, such as "Oh Susanna," "The Camptown Races," and "The Yellow Rose of Texas." As America changes, so do the lyrics with the removal of explicit racists terms and the dialect of slaves. A prime example of the lyrics' changing can be found in the "The Yellow Rose of Texas."

Earliest Minstrel versions began:

"There's a yellow rose in Texas that I'm going down to see / No other darkie knows her, no darkie only me ...."

During the Civil War, several versions were martialized:

A) "There's a yellow rose in Texas, that I'm going to see / No other darkie loves her, no darkie only me ...."

B) "There's a yellow rose in Texas this soldier's gonna see / No other soldier knows her, no soldier only me ...."

Present versions, as found in the 1955 Mitch Miller version, often begin:

"There's a yellow rose in Texas that I am gonna see / Nobody else could miss her not half as much as me"

Several sources argue that Minstrel Shows made it easier for African-American musicians to be accepted by whites in the 1890's. I am not convinced of this. However, Black historian Mel Watkins writing for The Smithsonian states,

"On stage you had white performers saying, 'Okay, we accept this type of music, we accept the antic performers,' and even though it was done in a ridiculing manner, there was some acceptance -- at least on stage. And by the 1860s black performers [were] going on the stage themselves and performing in a similar manner. Because basically when the black performers did minstrel shows, they were doing the same acts that whites had done before. It was necessary for them -- it was necessary for them to do that to be on stage. Otherwise, they would not have been allowed there. Gradually, they would change it, they would make modifications (PBS.org)."

These shows made possible acceptance by a wider America of African-American musicians, composers, and showmen. After the Civil War, minstrel shows were taken over and starred African-American performers singing and writing songs in this tradition through the 1930's. The question being asked is this, without Minstrel Shows, would the other 19th century musical genius--Black rag-time composer Scott Joplin--and 20th century's Cab Calloway and their works have been so readily accepted and loved by Americans of all races as there were. As jazz composer Nelson Riddle states, "There are two kinds of music--good and bad." People enjoy good music. When we enjoy the music, we tend to like the musicians.

Many Minstrel Show songs were also performed in homes as Parlor Music.

Parlor Music and the Minstrel Shows suffered major declines after the 1870's. As Mel Watkins mentions above, Black performers adopted much from the Minstrel performances. However, by the late 1870's Black musicians changed, remodeled, and merged the tradition until, to use a standard musical term, they "owned" the music. By the century's end the performers wrote and performed for Black audiences. Thus new music traditions evolved and added to the nation's musical forms.

The Music Hall style of music is a gift from the British, although the term Saloon Hall music is more appropriate for the United States. In addition to Saloon Halls, there grew in New York what was called Ice Cream Saloons in which patrons bought a dish of ice cream followed with a show, often a minstrel show. Few nations have mastered the Music Hall (which evolved into stage musicals) as have the British. In America just before and during the Civil War, Music Hall performances developed quickly into vaudeville and burlesque. The music allows for multiple voices and larger instrumental accompaniment. One branch of Music Hall evolved into movie soundtracks, in which American composers excel. Much familiar songs and tunes found in both Parlor Music and Minstrel Shows found their way onto the Music Hall stage. In America, Music Hall quickly turned into what became to be known as Tin Pan Alley.

Folk Music is difficult to label. It comes from spontaneous responses to the world of common folk. Melodies and tunes are borrowed from any source, one set of lyrics is altered to another, lyrics are modified at will to please either performer or audience, instrumentation is commonly whatever is affordable or available. There's no real unity at all or for that matter a definitive (or official) version. Performers and music arrangers often modified both lyrics and melodies to please themselves or their audiences. The element I like best is the directness of content and, at times, very powerful expression of emotion.

Gospel Music, known at this time as Sacred Music, is one expression of Protestant Christianity which has moved out of worship services into the community at large. Based on 4-part Bach harmony 2-4 eight-bar verses, and 1-2 four to eight-bar refrains, the music possesses a direct, driving melody. Verses are rhymed and easy to memorize. As the music moved out of churches, the harmonies moved into many directions that impacted other forms of music and poetry. While a number of songs are credited to Martin Luther and other Reformation leaders, Parlor Music influenced musical of Sacred Music. For example, Southern Blues is a descendant of Gospel harmonic progressions, and the poetry of Emily Dickinson can be easily focused by viewing them as hymns. Although the term "gospel music" only appeared in the mid 1870's, the music itself had been around for nearly two centuries. Many Parlor music songs, including a number of those by Stephen Collins and George Root, are religious in nature. Following the Civil War, Root wrote religious lyrics for a number of his war-time melodies.

We need to remember that all these forms overlap and are not necessarily 'pure' in description. The wealth and abundance of these forms should not be ignored. The Frontier experience is hugely recorded or represented. Stephen Collins Foster, took the music from the British Isle and smashed them against the Frontier, creating a musical forms that were distinctly American. The music and lyrics have cultural impact that went beyond performance (An example is the Civil War ballad "All Quiet on the Potomac." The effect of the song often led to both Union and Confederate commanders to forbid sniping between pickets on duty at night. The song also inspired the German novel, All Quiet on the Western Front). The music and, for this class, the lyrics become a dynamic portion of our literary heritage.

The video below is a clip from a film about E. P. Christie, one of the early--if not the first--black face performers, starring Al Jolson. The film was mainly about the man but contains black face performances, using stage performances in the historical setting. Note the use of heavy, exaggerated makeup which is unlike the burnt cork makeup in Christie's and Foster's time. Like Stephen Foster's music, Christie's Minstrels developed in Cincinnati and New York. To deny the historical events and the effects that follow is intellectual fraud. Nonetheless, it's unthinkable in the 21st century to image such a stage show being performed such as this today.

Popular music flourished during the Romantic Period and the Civil War. America failed to produce classical composers with the quality of Strauss, Wagner, or Verde, but the popular music field gave birth to composers and poets who produced a wealth of tunes, lyrics, and traditions that resonate to this day. The roots of jazz, screen and stage soundtracks, the Blues, and rock and roll have their origins from this period. Of course, these forms of music do have deep roots from Europe and African, but they developed in the rich soil of the New World. Nevertheless, it was during this time that an American musical identity became established.

It is important to remember that these divisions are, in some ways, arbitrary. It very common to find parlor songs, for example, performed in Saloon Halls, Opera Houses, on the Oregon and Sante Fe Trails, and (religious songs) in churches. The crossovers were common.

Parlor Music is a form with roots in the 18th century. This activity seems almost too hokey to be real, but it provided pleasure and enjoyment for millions. Small groups of family and/or friends would perform, in their parlors of course, music that is melody centered. Various (or none) musical instruments would accompany the vocals. Often, music was strictly instrumental or vocal only. The music was commonly for a single voice (alto or tenor) with piano accompaniment. However, the music was adaptable for various instruments. Stephen Foster's music was uncommon, for he often wrote choruses for 4 part harmony. The high demand for music maintained music publishers all throughout America. Parlor music gave rise to the first true American music. Many songs were adapted for public performances. Some composers, like Foster, wrote songs that went easily from Parlor to Saloon Hall to Minstrel Show.

Some music and lyrics go back to the Revolutionary War and War of 1812 periods. One example is "Johnnie has Gone for a Soldier," which has roots in Ireland or Scotland (there's argument here; perhaps found in both?). The Scottish immigrants were more numerous and actively involved in the Revolution than the Irish, so I think the song came to the New World from Scotland even if it originated in Ireland. Regardless, this beautiful lament remains well known here at the beginning of the 21st century. The lyrics sung by Erin Ivey (below) are one of the many versions available, but the words are very close. Minor changes in lyrics, melody, and rhythm by each performer is a norm in the world of music performance.

Minstrel Shows seem to us today as unbelievable or even impossible. The right and wrong of it is not the discussion here. The Minstrel Show was also known as "Black Face," for white musicians and actors would paint their faces black in imitation of African-Americans -- particularly of those who were enslaved. These shows were performances although the songs frequently were published and sung in parlors as well as Music Halls. Minstrel Shows were first recorded in a music hall when Tom Rice Dixon, it is said, literally borrowed the clothes from a Black laborer, charcoled his face to perform an "Ethiopian" song. Many composers, however, were familiar with the church and secular music of free blacks. This was an influence, not copying as Modernist musicians argued in the 1930's. Stephen Foster, as an example, irritated his parents by sneaking off to listen to the Black laborers and performers near the docks and warehouses near his home. A free-Black maid in the Foster house often took the child Foster with her to local AME church services. This influence would be similar to the effects the Blues had upon the young Elvis Presley. During the first half of the 19th century, the minstrel shows went through three phases. In phase one, the performers presented skits and songs, while denigrating African Americans as ignorant and childlike, also rediculed Irish and German immigrants and the upper classes of the Industrial Revolution. In the second phase, the shows became more gentile for various reasons. The minstrel producer E. P. Christie and his Christie Minstrels and others wanted a broader more gentile paying audience than had been before. This coincides with Stephen Foster's attitude shifts. In partnership with Christie his music presents a human and sympathetic person. Examples of his songs include "Nellie Was A Lady," "My Old Kentucky Home." and "Old Folks at Home." Phase three in the mid to late 1850's turned vicious as tensions just before the Civil War heated up. At this point Foster quit writing his Plantation Songs and Christie retired.

Incredibly, these types of shows remained popular through the early 1960's [I myself took part of one these programs in grade school program in the sixth grade in Denton, TX. I was the only child not in black face as I was the 'ringmaster']. The BBC had a variety series, Black and White, that continued this tradition to the 1970's. The first important 'talking' movie was The Jazz Singer in which the finale is a black face performance by Al Jolson. Was this musical form racist? Of course it was. Nonetheless, many classic tunes that we are familiar with have roots here, such as "Oh Susanna," "The Camptown Races," and "The Yellow Rose of Texas." As America changes, so do the lyrics with the removal of explicit racists terms and the dialect of slaves. A prime example of the lyrics' changing can be found in the "The Yellow Rose of Texas."

Earliest Minstrel versions began:

"There's a yellow rose in Texas that I'm going down to see / No other darkie knows her, no darkie only me ...."

During the Civil War, several versions were martialized:

A) "There's a yellow rose in Texas, that I'm going to see / No other darkie loves her, no darkie only me ...."

B) "There's a yellow rose in Texas this soldier's gonna see / No other soldier knows her, no soldier only me ...."

Present versions, as found in the 1955 Mitch Miller version, often begin:

"There's a yellow rose in Texas that I am gonna see / Nobody else could miss her not half as much as me"

Several sources argue that Minstrel Shows made it easier for African-American musicians to be accepted by whites in the 1890's. I am not convinced of this. However, Black historian Mel Watkins writing for The Smithsonian states,

"On stage you had white performers saying, 'Okay, we accept this type of music, we accept the antic performers,' and even though it was done in a ridiculing manner, there was some acceptance -- at least on stage. And by the 1860s black performers [were] going on the stage themselves and performing in a similar manner. Because basically when the black performers did minstrel shows, they were doing the same acts that whites had done before. It was necessary for them -- it was necessary for them to do that to be on stage. Otherwise, they would not have been allowed there. Gradually, they would change it, they would make modifications (PBS.org)."

These shows made possible acceptance by a wider America of African-American musicians, composers, and showmen. After the Civil War, minstrel shows were taken over and starred African-American performers singing and writing songs in this tradition through the 1930's. The question being asked is this, without Minstrel Shows, would the other 19th century musical genius--Black rag-time composer Scott Joplin--and 20th century's Cab Calloway and their works have been so readily accepted and loved by Americans of all races as there were. As jazz composer Nelson Riddle states, "There are two kinds of music--good and bad." People enjoy good music. When we enjoy the music, we tend to like the musicians.

Many Minstrel Show songs were also performed in homes as Parlor Music.

Parlor Music and the Minstrel Shows suffered major declines after the 1870's. As Mel Watkins mentions above, Black performers adopted much from the Minstrel performances. However, by the late 1870's Black musicians changed, remodeled, and merged the tradition until, to use a standard musical term, they "owned" the music. By the century's end the performers wrote and performed for Black audiences. Thus new music traditions evolved and added to the nation's musical forms.

The Music Hall style of music is a gift from the British, although the term Saloon Hall music is more appropriate for the United States. In addition to Saloon Halls, there grew in New York what was called Ice Cream Saloons in which patrons bought a dish of ice cream followed with a show, often a minstrel show. Few nations have mastered the Music Hall (which evolved into stage musicals) as have the British. In America just before and during the Civil War, Music Hall performances developed quickly into vaudeville and burlesque. The music allows for multiple voices and larger instrumental accompaniment. One branch of Music Hall evolved into movie soundtracks, in which American composers excel. Much familiar songs and tunes found in both Parlor Music and Minstrel Shows found their way onto the Music Hall stage. In America, Music Hall quickly turned into what became to be known as Tin Pan Alley.

Folk Music is difficult to label. It comes from spontaneous responses to the world of common folk. Melodies and tunes are borrowed from any source, one set of lyrics is altered to another, lyrics are modified at will to please either performer or audience, instrumentation is commonly whatever is affordable or available. There's no real unity at all or for that matter a definitive (or official) version. Performers and music arrangers often modified both lyrics and melodies to please themselves or their audiences. The element I like best is the directness of content and, at times, very powerful expression of emotion.

Gospel Music, known at this time as Sacred Music, is one expression of Protestant Christianity which has moved out of worship services into the community at large. Based on 4-part Bach harmony 2-4 eight-bar verses, and 1-2 four to eight-bar refrains, the music possesses a direct, driving melody. Verses are rhymed and easy to memorize. As the music moved out of churches, the harmonies moved into many directions that impacted other forms of music and poetry. While a number of songs are credited to Martin Luther and other Reformation leaders, Parlor Music influenced musical of Sacred Music. For example, Southern Blues is a descendant of Gospel harmonic progressions, and the poetry of Emily Dickinson can be easily focused by viewing them as hymns. Although the term "gospel music" only appeared in the mid 1870's, the music itself had been around for nearly two centuries. Many Parlor music songs, including a number of those by Stephen Collins and George Root, are religious in nature. Following the Civil War, Root wrote religious lyrics for a number of his war-time melodies.

We need to remember that all these forms overlap and are not necessarily 'pure' in description. The wealth and abundance of these forms should not be ignored. The Frontier experience is hugely recorded or represented. Stephen Collins Foster, took the music from the British Isle and smashed them against the Frontier, creating a musical forms that were distinctly American. The music and lyrics have cultural impact that went beyond performance (An example is the Civil War ballad "All Quiet on the Potomac." The effect of the song often led to both Union and Confederate commanders to forbid sniping between pickets on duty at night. The song also inspired the German novel, All Quiet on the Western Front). The music and, for this class, the lyrics become a dynamic portion of our literary heritage.

The video below is a clip from a film about E. P. Christie, one of the early--if not the first--black face performers, starring Al Jolson. The film was mainly about the man but contains black face performances, using stage performances in the historical setting. Note the use of heavy, exaggerated makeup which is unlike the burnt cork makeup in Christie's and Foster's time. Like Stephen Foster's music, Christie's Minstrels developed in Cincinnati and New York. To deny the historical events and the effects that follow is intellectual fraud. Nonetheless, it's unthinkable in the 21st century to image such a stage show being performed such as this today.

Video clip used under Fair Use Law

Colonial Music & Early Republic

|

I chose this version, for the lyrics here seem to have been commonly sung from about 1750 - 1812. The version above is sung in English and Gaelic. I have to date found at least nine different variations. This performance by Erin Ivey is one of many styles of performing; this one is a lament rather than a ballad.

Johnnie Has Gone For A Soldier (Late 18th century) (Composer / Lyricist Unknown) Here [Sad] I sit on Buttermilk [yonder] Hill Who can blame me, cryin' my fill And ev'ry tear would turn a mill Johnny has gone for a soldier Me, oh my, I loved him so Broke my heart to see him go And only [They say that] time will heal my woe Johnny has gone for a soldier [A blessing walk with you, my love] [Sung in Gaelic] Shule, shule, shule agra Time can only heal my woe Since the lad of my heart from me did go Johnny has gone for a soldier I'll sell my flax [rod] and my spinning wheel To buy my love a sword of steel So it in battle he might wield Johnny has gone for a soldier With fife and drum he marched away He would not heed what I did say He'll not come back for many a day Johnny has gone for a soldier I'll sell my flax and my spinning wheel To buy my love a sword of steel So it in battle he might wield Johnny has gone for a soldier I'll dye my dress, I'll dye it red, And through the streets I'll beg for bread, For the lad that I love from me has fled, Johnny has gone for a soldier. Oh my baby, oh my love Gone the rainbow, gone the dove Your father was my one [only], true love Johnny has gone for a soldier Shule, shule, shule agra Time can only heal my woe Since the lad of my heart from me did go Johnny has gone for a soldier Johnny has gone for a soldier Johnny has gone for a soldier Source: The American Songbook, 1881. |

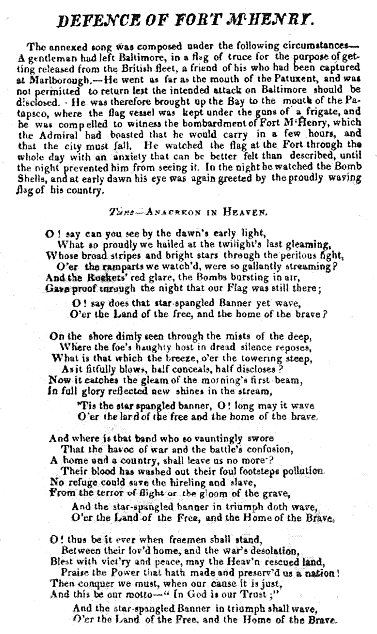

Now the official national anthem, Francis Scott Key wrote the poem after watching the bombardment of Fort McHenry by the British navy who failed in their attempt to subdue the fort as a necessity to attack Baltimore. The melody was based the tune to "To Anacreon in Heaven" by John Stafford Smith, about 1780.

The Star Spangled Banner (1814) Francis Scott Key Oh, say can you see by the dawn's early light What so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming? Whose broad stripes and bright stars thru the perilous fight, O'er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming? And the rocket's red glare, the bombs bursting in air, Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave? On the shore, dimly seen through the mists of the deep, Where the foe's haughty host in dread silence reposes, What is that which the breeze, o'er the towering steep, As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses? Now it catches the gleam of the morning's first beam, In full glory reflected now shines in the stream: 'Tis the star-spangled banner! Oh long may it wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! And where is that band who so vauntingly swore That the havoc of war and the battle's confusion, A home and a country should leave us no more! Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps' pollution. No refuge could save the hireling and slave From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave: And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! Oh! thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand Between their loved home and the war's desolation! Blest with victory and peace, may the heav'n rescued land Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation. Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just, And this be our motto: "In God is our trust." And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! Source: The Library of Congress; National Archives

|